USA, Decade Of Neglect Has Weakened Federal Low-Income Housing Programs

New Resources Required to Meet Growing Needs

by Douglas Rice and Barbara Sard

A large and growing number of low-income renters face unaffordable housing costs. Federal housing programs have proven effective in enabling millions of low-income households to obtain stable, decent housing, but a funding squeeze and various actions taken by Congress and the Bush Administration have weakened these programs considerably, just when the need is rising. This report documents that growing need, explains how federal housing programs help address it, shows how recent funding shortfalls and policy changes have hurt these programs, and outlines a series of steps to make housing more affordable for low-income families.

Executive Summary

One-third of all American households are renters, as are about half of low-income households. Yet too many renters pay housing costs that are unaffordable. The problem has grown in recent years, according to Census data, and is especially acute among households with the lowest incomes:

- More than 8 million renter households paid more than half of their income for rent and basic utilities in 2007 , the most recent year for which data are available. Under federal standards, housing costs are considered unaffordable if they exceed 30 percent of household income. (See Appendix A for state by state data on housing cost burdens.

- Nearly all of these households had low incomes (i.e., at or below 80 percent of their state’s median income). Two out of three of them had extremely low incomes (i.e., below 30 percent of the state median income, a level that is roughly equivalent to the federal poverty line).

- The number of low-income renter households that paid more than half of their income for housing increased by 2 million, or 32 percent, between 2000 and 2007.

- Many of these households are working households. Excluding those headed by people who are elderly or have disabilities, low-income households that pay more than half of their income for housing report that members worked a combined average of 25 hours per week for 25 weeks during the prior year.

When housing costs are too high, the impact on low-income renters can be severe and enduring. Families can be forced to cut back on food, clothing, medications, or transportation. High housing costs also can compel families to live in housing that is overcrowded or unhealthy, or in neighborhoods with failing schools, high rates of crime, or limited access to basic services. Moreover, research suggests that housing instability and homelessness can hinder the healthy development of children in ways that have a lasting impact.

This problem is likely to get worse. Over the past decade, the number of renter households has grown faster than the supply of rental housing, and there is little reason to expect this trend to change in the near future. Although rents may decline in some communities as a result of the foreclosure crisis and recession, wages will fall as well and unemployment is already rising.

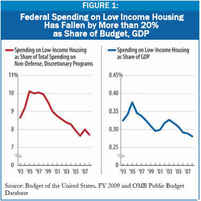

Yet despite rental housing’s importance to the well-being of a large share of American households — and the clear failure of the private market to meet the existing need — it has been the neglected step-child of federal housing policy. Since 1995, federal spending on low-income housing assistance has fallen by well over 20 percent both as a share of all non-defense discretionary spending and as a share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Even when combined with the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, the federal government’s total commitment to low-income housing assistance is less than one-third the size of the three largest tax breaks provided to homeowners (such as the home mortgage interest deduction).

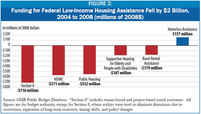

The fiscal pressure on low-income housing programs increased considerably during the Bush Administration. The Administration’s annual budgets gave priority to deep tax cuts and increases in defense and homeland security funding. When sizeable deficits emerged in 2003 and 2004, the Administration and Congress turned primarily to reductions in domestic discretionary (i.e., non-entitlement programs). Discretionary funding for federal low-income housing programs, for example, was slashed in 2005; after rising modestly in 2006 and 2007, it fell again in 2008. In 2008, total funding for all low-income housing programs was $2.0 billion (5.0 percent) below the 2004 level, adjusted for inflation. For some programs, such as public housing, these cuts came on top of earlier funding reductions. (See Figure 2 below.)

These reductions in funding, combined in some cases with policy changes that exacerbated funding instability, have weakened the three major federal low-income housing programs at a time when the need for assistance is rising sharply:

- Housing Choice Vouchers. This program provides about 2 million low-income families with vouchers to help pay for housing that they find in the private market. More than half of these families include children; another third include seniors or people with disabilities. Between 2004 and 2006, voucher assistance for approximately 150,000 low-income families was eliminated as funding shortfalls compelled housing agencies to serve fewer families. Many agencies also cut costs in other ways that have discouraged landlords from renting units to families with vouchers and limited the ability of families to use vouchers to move to neighborhoods with lower crime rates and better schools.

- Public Housing. The nation’s 14,000 public housing developments, located in more than 3,500 communities, provide affordable homes to nearly 1.2 million families, nearly two-thirds of which include seniors or people with disabilities. In recent years, deep and persistent funding shortfalls have forced housing agencies to take steps such as increasing costs for low-income tenants, delaying repairs, and cutting back on security. Also, an increasing number of agencies appear to have concluded that they can no longer sustain all of their developments and are seeking to remove them from the program. Some 165,000 units of public housing have been lost since 1995 and not replaced; these losses are likely to continue.

- Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance. This program is a public-private partnership in which private owners sign contracts with HUD to provide affordable homes to nearly 1.3 million low-income families, three-quarters of which are headed by people who are elderly or have disabilities. Over the past few years, a series of changes in HUD funding policies — designed in part to save money — caused widespread and lengthy delays in payments to owners and have undermined confidence in this program. Some 10,000 to 15,000 units of affordable Section 8 housing are lost every year as owners exit the program; these losses are likely to accelerate if HUD fails to restore owner confidence. At greatest risk are approximately 150,000 units whose owners already have strong financial incentives to leave the program because the rents they receive are well below market rates.

Only one in four low-income households eligible for federal housing assistance receives it because of funding limitations. Unless the new Administration and Congress set a different course, an even smaller proportion of the low-income households is likely to be assisted in the future, further widening the gap between housing needs and available federal assistance.

New Resources Required to Address Growing Needs

Following nearly a decade of neglect — and the bursting of the housing bubble, which has exposed the limitations of an unbalanced emphasis on homeownership — it is time for the new Administration and Congress to revitalize federal rental housing policy. Policymakers need to develop a comprehensive strategy to address the private market’s failure to provide sufficient affordable housing. But in the meantime, they should pursue the following goals, which should form part of any viable comprehensive strategy:

Preserve existing public and private assisted housing , in its current location or in other locations that will better serve families. Specifically, the Administration and Congress should commit the necessary resources to:

- Restore full operating funding for public housing;

- Address the substantial backlog of capital repairs in public housing;

- Re-establish reliable renewal funding for project-based Section 8 contracts;

- Provide incentives and assistance to encourage private owners to renew their participation in the Section 8 project-based rental assistance program; and

- Improve energy efficiency in public and private assisted housing.

Fully utilize the housing vouchers Congress has already authorized. Enacting the funding provisions of the Section 8 Voucher Reform Act (SEVRA), which the House passed in 2007, would encourage housing agencies to use voucher funds more efficiently. As a result, significantly more low-income families would receive voucher assistance. No additional funding would be required in the first year these vouchers were used.

Expand assistance to help more families secure stable, affordable housing in safe neighborhoods with access to good schools, steady jobs, and other essential services they need to improve their lives. The most flexible, cost-effective way to do this is to fund new, “incremental” housing vouchers. Two million new vouchers (for example, funding 200,000 new vouchers per year over ten years), would help roughly 3 million low-income households over the 10-year period to secure decent, affordable homes; lift an estimated 3.3 million people, including 1.6 million children, out of poverty; and prevent 230,000 people, including 110,000 children, from becoming homeless [1]. New vouchers could also be used to promote other policy goals, such as the development of affordable housing near mass transit (to reduce energy use and promote climate change goals) or as part of a broad strategy to expand educational and economic opportunities for low-income families.

To expand housing voucher assistance to 2 million new families would require a substantial investment: roughly $8,000 for each voucher in the first year, plus the cost of renewal of each voucher in subsequent years. This investment would pay considerable dividends, however, in terms of reduced poverty and homelessness and better opportunities for families struggling to improve their lives while making ends meet.

[1] These figures reflect the benefits only in the first ten years.

Full report:

http://www.cbpp.org/2-24-09hous.htm