Kanal İstanbul: a “crazy project” serving political ambitions

The current proliferation of mega-projects in the Istanbul metropolitan area is both undeniable and impressive. The projects currently in progress or scheduled for the near future will impose long-lasting changes on the urban structure of this megalopolis. Yoann Morvan, a researcher and co-director of the Observatoire Urbain d’Istanbul (Istanbul Urban Observatory), analyses these territorial metamorphoses and highlights the electoral and economic factors that come into play behind the scenes.

On 12 June 2011, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his party achieved a clear victory in Turkey’s legislative elections, obtaining half of all votes – their third consecutive win since 2002. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) owes this level of public approval in no small part to the success of the Turkish economy (9% growth in 2010, just behind China), of which Istanbul is the driving force.

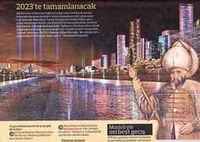

Erdoğan, a former mayor of Istanbul, intends to maximise the city’s economic potential through a number of mega-projects. The Turkish prime minister launched his campaign (on 27 April 2011) with the announcement of, in his own words, a “crazy project”: the creation – in time for 2023, the centenary of the creation of the Republic of Turkey – of a canal 50 km long, 25 m deep and 150 m wide, linking the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara.

The “kanal”: creating new focal points in the city

For a total estimated cost of $10–20 billion, the “kanal” would bring about a radical transformation of the project site and a restructuring of the Istanbul metropolitan area. This “new Bosphorus” would turn the majority of the built-up area on the European side into an artificial island and would help generate or reinforce new focal points to the north and west of the current metropolitan area. It represents the culmination of a series of major projects: a new airport (the biggest in Turkey), a port, extensive residential and business districts and two new towns – one on each side of the Bosphorus. Above all, the canal is part of a wider project involving the construction of a new bridge over the strait that will form the final link of a new 260 km orbital motorway, with the whole project set to cost more than $6 billion.

The canal mega-project would expand the economic and urban potential created by the construction of the new bridge, announced a year earlier (on 29 April 2010) by the transport minister and intended – according to the minister himself – to facilitate road freight movements through Istanbul. The existing routes far to the north of the new bridge and the orbital motorway were already part of a strategy to open up this particularly fast-growing area on the edge of the conurbation (Montabone & Morvan 2011). The canal would considerably broaden horizons in this regard, and at the very least put Erdoğan’s environmental arguments [1 ] in favour of this new infrastructure into perspective.

Specious environmental arguments

For the prime minister, the primary justification for the multifaceted “kanal İstanbul” project lies in the undeniable environmental risks that come with an increase in traffic on the Bosphorus – cargoes, supertankers, tens of thousands of ships transporting, according to Erdoğan, 140 million tonnes of oil. The new canal would provide a passageway for up to 160 boats per day, which would seem to be sufficient to relieve congestion on the Bosphorus, which has been the site of two major accidents involving oil tankers, in 1979 and 1994, causing 41 and 28 deaths respectively along its sinuous 32-kilometre (20-mile) course. However, although the danger of the Bosphorus, with its many currents, is very real (Bazin & Pérouse 2004), the canal does not seem capable of providing a sustainable alternative.

Indeed, the project has attracted almost universal disapproval from independent experts. [2 ] Like the third bridge over the Bosphorus, the “kanal” would, at best, only displace or limit the growth of a certain number of environmental problems and divide the risk between the two waterways. The environmental argument is all the more fallacious given that most studies [3 ] have shown that the creation of a new transport infrastructure generally tends to lead to an overall increase in traffic without significantly relieving existing traffic problems, resulting in even more pollution. And in terms of risk, the hypocrisy is even more striking: if having supertankers pass through the middle of a city of 13 million people is dangerous, why schedule massive urban development alongside a new canal and create two new towns in the vicinity?

At this point, another type of argument also comes into play: seismic risk. As Istanbul is, in theory, likely to experience a large-scale earthquake at some point in the next few years, Erdoğan plans to rehouse part of the population living in the most exposed areas in these new neighbourhoods that are to be developed. This proposal has been dismissed by specialists, such as Tayfun Kahraman, [4 ] for whom the priority should instead be to take care of existing housing before even thinking about plans that specifically seek to expand the conurbation. The arguments relating to the environmental risks are simply a smokescreen masking the massive financial stakes of the mega-projects led by the Justice and Development Party.

Mega-promotions: property and politics

In a successful bid to satisfy the many businessmen close to the AKP, Erdoğan promised that the development of new residential areas and motorways alongside the canal would lead to significant profits, particularly through public–private partnerships. Beyond the immediate vicinity of the canal and its road connections around Silivri et Çatalca, [5 ] a large section of north-western Istanbul would stand to benefit from all the mega-projects mentioned above. The interests of the powerful individuals present in this large area are considerable, either directly in the case of Arnavutköy, where the prime minister’s family has invested a great deal, or indirectly in the case of the giant pseudo-social housing projects built for TOKİ (the Turkish Housing Development Administration) in Başakşehir – veritable Trojan horses in the form of public property promotion on a monumental scale.

The thousand or so AKP members gathered for the announcement of the “crazy project” chanted “Turkey is proud of you!”, while the party leader himself declared that “we shall all roll up our sleeves for the Kanal İstanbul, one of the greatest projects of the century, set to surpass even the Panama and Suez Canals”, comparing his dream to the creations that Ottoman architect Atik Sinan built for Fatih Sultan Mehmet (Mehmed II the Conqueror), who brought the Byzantine Empire to an end in 1453. By flattering the national sentiment of his compatriots in this way with a speech peppered with touches of neo-Ottomanism, Erdoğan also sought to “seduce” supporters of the far-right party MHP, which was undergoing something of a crisis at the time of the election campaign. On the international diplomatic scene, the “kanal” – a potential rival to the Nabucco gas pipeline and Russian energy companies – has raised a number of concerns: would it not go against the Montreux Convention of 1936 regarding free passage via the Bosphorus? The new canal – a toll waterway – would attract shipowners wishing to reduce journey times. The prime minister’s aim is to make Turkey one of the top 10 world economies in time for the centenary of the modern Turkish state in 2023.

In the meantime – and until the construction of a canal to rival the Bosphorus becomes a reality – an imitation Bosphorus has already been created: “Bosphorus City”. This luxury property development, promoted by the singer Julio Iglesias and designed by Albert Speer Jr (the son of the architect of the same name who worked under Hitler), would not look out of place in Las Vegas, Dubai or China. Of course, Bosphorus City will no doubt pale in comparison to the mammoth project that is the future “Kanal İstanbul”, along with its juicy economic and political gains...

Further reading

- Bazin, Marcel and Pérouse, Jean-François. 2004. “Dardanelles et Bosphore : les détroits turcs aujourd’hui”, Cahiers de géographie du Québec , vol. 48, no. 135, pp. 311–334. URL: www.erudit.org/revue/cgq/200... .

- Morvan, Yoann and Montabone, Benoît. 2010. “Le pont de la rente. Les enjeux fonciers du troisième pont sur le Bosphore à Istanbul”, Études foncières , no. 148, November/December 2010.

- Montabone, Benoît and Morvan, Yoann. 2011. “Istanbul : la carte du troisième pont sur le Bosphore”, EspacesTemps.net , Mensuelles, 18 avril. Consulté le 6 décembre 2011. URL: http://espacestemps.net/document878... .

- (Promotional) video of Bosphorus City: http://www.moodproduction.com/index... .

- Website presenting the projects in Başakşehir: http://www.istanbulthemepark.net/en... .